Up until now,

I have stuck to one story, or one segment of a trip, per post. With this one, I want to do something a little differently, for a couple of reasons.

First, I have multiple small stories I want to tell you, but none of them are big enough on their own for a single post. So I have decided to bunch some stories that have a common theme together in this one post.

And second, although most of my posts will be about international travel, this one will be about local travel – within my home province of Alberta, in Canada.

I enjoy chasing clear night skies, especially with my camera! Night photography presents varying degrees of thrill. The most random chases are for Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights), Meteor Showers, & Lightning. With the rest, I usually have an idea of what constellations or events I am expecting to see that night. But surprises are exciting, and are usually welcome! The biggest challenge is avoiding clouds. Because if I can’t see the sky, no matter what’s happening up there, for all intents and purposes I am blind. Exceptions to this include rare occasions when clouds block some bright light source (usually the moon), or when I am shooting lightning (for that I definitely need clouds). Storm chasing usually takes a lot of luck or some major planning! To effectively shoot lightning, I want to be as near to the storm as possible, because the closer I am, the bigger the lightning will be in my pictures. But I don’t want to be so close that my gear and I are getting rained on, or are at risk for attracting said lightning!

Over the years, I have successfully shot Iridium Flares, Northern Lights, the Milky Way, Comets, Meteor Showers, Planetary Conjunctions, Solar & Lunar Eclipses, Lightning, & more.

I have some great news to share with you!

I’m rolling out a new feature on this blog, starting with select pictures in this post. Look out for this in future posts as well!

Some of my pictures are best viewed in high resolution. I have only uploaded low-res versions here in my blog, to keep it quick loading. But with select pictures, if you click on them, you’ll be taken to a high-resolution version in a new tab, hosted on another site called “Clickasnap”. I will mention which images this applies to in the captions. Also, here’s a link to my Clickasnap profile.

I’d like to point out another thing.

In astronomy, apparent magnitude (most times referred to simply as “magnitude”) is a measure of the brightness of an object as it appears in the night sky from Earth. The scale appears to work ‘in reverse’, wherein objects with a negative magnitude are brighter than those with a positive magnitude. And the more negative the value, the brighter the object.

For more detailed information, please check out this Wikipedia article (which is also my source for this paragraph).

How well we can see the objects in the night sky depends on how much light pollution is present at the viewer’s location. There are a few websites and apps that make this information available, here’s my favorite one: Light Pollution Map. Sadly, Alberta is one of the most light-polluted provinces in all of Canada. The light here is so bright and seems to cover all but the most remote of regions. But I do my best to get out and see what I can.

One of the first things I shot at night was Iridium Flares.

These are the satellites that form one of the worldwide networks for sat phones. Fun fact: there are 66 satellites in the constellation. They were named “Iridium” because it was first thought that the constellation would require 77 satellites. And the element iridium is number 77 in the periodic table of the elements. When I started paying attention to astronomy, they had already been up for a while, as the first batch was launched in 1997. The fact that they “flared” was a happy accident, they weren’t sent up for that purpose. The flares happened due to sunlight reflecting off the satellite’s highly reflective antennas. Because they were in stable and known orbits, it was relatively easy to predict where to see the flares. A couple of websites and apps used that data, along with the viewer’s location, to show where and when to look in the sky. I even used my app and observed some while I was travelling in Australia! Over the years, I observed 22 Iridium Flares (most in Alberta), but I only captured 5 with my camera (all in Alberta, and after I returned from Australia). I wanted to shoot more photos, but unfortunately, I was unable to get out frequently due to interference from clouds and my job at the time. Then they were de-orbited to make way for the next generation of Iridium satellites; and sadly, the new ones didn’t flare. Some of the flares were very bright, and others were so dim that they were barely visible. How bright they appeared depended on how close the viewer was to the satellite’s path of travel.

Seeing the core of the Milky Way requires a truly dark area free of light pollution.

Because cameras are more sensitive than human eyes, pictures of the core can sometimes be taken even if it’s not visible. But it is very special to stand under a dark sky and see the core of the Milky with so many stars visible! Here are some pictures I took while I was hiking with friends near Jasper, AB. We stayed in a beautiful little cabin that we rented! It’s called the Fryatt Hut and it is owned, maintained, & rented by the Alpine Club of Canada. For more information, please check out their website.

The nearest light was in the town of Jasper, and we were many kilometers away, with mountains between. What I mean is that we were in a well-isolated place, that was truly dark at night.

That same night, just a little bit after taking pictures of the Milky Way, we were pleasantly surprised by a gorgeous display of Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights)! I just love this image, of all the pictures I have taken of the Northern Lights so far, this one is my favorite! Then I decided to do a self portrait, which turned out great!

Another place that I have shot some Northern Lights

is at Astotin Lake, in Elk Island Park. But this place has grown in popularity. Usually now when something is happening up in the sky, and the clouds are cooperative and stay away, all the good spots in the park get filled up with so many people! The last time I got some good shots there was back in 2017. I personally feel that it’s more productive to find a quiet spot along a country road than to go where so many of the masses go! As long as I don’t point my camera back towards the city, I usually have a pretty dark sky to work with.

Green is the most common and visible color. If there was high solar activity, then we might see other colors, including purple, blue, pink, or yellow. The rarest color, red, only has the possibility to occur if the solar activity was intense! I have never personally seen red Northern Lights yet, but I hope to one day.

Lightning is by far the most powerful subject I’ve ever shot!

The difficulty and challenge of capturing this subject, I find, causes me to enjoy my good shots that much more. And no two shots are the same, there’s a wonderful randomness to shooting lightning.

I have tried a few times to shoot some meteor showers,

but so far with limited success. This is the only meteor I have successfully shot, and it’s very dim. My limited success is partially due to the lenses that I have been using so far. I have been using my “kit lens” which doesn’t let in as much light as other (more expensive) lenses. I recently acquired a lens specifically made for nighttime shooting, and I am looking forward to seeing what kind of pictures I will be able to take with it.

Seeing, and shooting, Comet Neowise

(C/2020 F3) was a unique experience because it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. It was one of the brightest comets seen for decades, and it won’t come back around to earth for almost 7000 years; it’s said that the next time it’s visible from the earth again will be in the year 8786! It was visible to the naked eye, which is a rare treat for a comet. Although I did see it with just my eyes, seeing it in my binoculars and through my camera lens made it even better by bringing out more detail. This next photo shows a more zoomed-out view, but it looked a little bit smaller than this to the naked eye.

Sometimes while driving in the wee hours of the morning,

I come across a photo opportunity that I hadn’t planned on. That’s what happened with this rail trestle. As I drove past it, I saw in my mind the kind of shot I wanted to try to get. Once I found a place with the correct perspective to shoot from, I brought my imagination to life! This time it worked out great, but it doesn’t always go how I think it might. That’s the joy of digital photography, I have the freedom to try different things. I don’t need to spend money developing my shots to see if they worked out.

Most times,

when there’s something that we deem “important” that’s going to happen in the night sky, there’s a buildup. It’s also usually predicted long before we get to the point of actually seeing it. Due to the orbital nature of how things move in space, whatever we are watching (comets, planets, stars, satellites, eclipses, meteor showers, etc.) can sometimes first become visible far from their predicted places. Then we might get to watch them move towards their final predicted spot; before the moment passes and the night sky once again becomes quotidian. Depending on what we are watching, this “dance” can take months, weeks, hours, or mere seconds to get to the predicted event (usually it’s satellites that move so quickly, giving us only seconds, most everything else gives us more time). The event itself may last for seconds, minutes, or hours. Unless we are talking about something like when the core of the Milky Way or certain heavenly bodies are visible, those are usually measured in months. There are so many variables! We may be watching two heavenly bodies move close together in a conjunction; a comet move closer to earth, becoming brighter and more visible; a heavenly body that only becomes visible when the earth is tilted a certain way on its axis, which coincides with a certain season; an annual meteor shower; an eclipse; or something else entirely.

Near the event, it’s vital to check the weather. Clouds can dictate that you may need to travel in order to see the sky, or they can completely block your view.

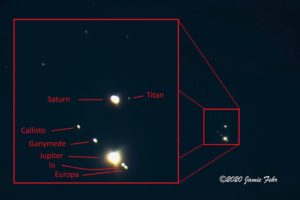

My photos of the Saturn & Jupiter conjunction of 2020 were actually taken on the day before they were the closest together. I had checked the weather, and the prediction for the next night was that most of Alberta would be under a very heavy cloud cover. So I went out when I had clear skies. That was a good thing, because the weatherman was correct that time! The next night, nearly the entire province was under almost 100% cloud cover. This particular conjunction took a few weeks to build up to the event (the time when they were closest), then over the next few weeks, they appeared to drift apart again.

The last thing that I’ll share with you

is some of the eclipses that I have photographed. So far, I have witnessed 2 partial solar eclipses and 3 total lunar eclipses. One day I hope to observe a total solar eclipse. These events are quite fascinating to watch as they unfold right in front of your eyes! A solar eclipse is when the moon moves between the earth and the sun. And a lunar eclipse is when the earth moves between the sun and the moon. For a more thorough explanation, please check out this Eclipse Guide. Of all the things I have covered in this post, the only thing that will slightly stray from the Night Sky theme is the solar eclipses, because it’s impossible to see the sun at night. To shoot a solar eclipse I am required to point my camera directly at the sun. Warning: If you ever point your camera at the sun, NEVER look through the lens at the sun, you could blind yourself; instead, use live view and the screen. Also, cameras aren’t made to handle the magnified heat of the sun coming through the lens for very long periods of time, internal damage can occur. I had my lens cap on for the entire duration, except when I was taking the actual shot. There are special filters that you can get, but I currently don’t have any. Here’s an interesting fact: because the sun is so bright & overpowering, a thin cloud layer between the sun & my camera actually helps me to get better pictures; but it can’t be too thick, or it blocks the sun out completely. I will demonstrate this with a couple of photos.

The lunar eclipses I shot were with an older camera, so the picture quality isn’t as good as the rest of my pictures. Did you know that only when the earth’s shadow fully covers the moon does it look red, and this is sometimes referred to as a “blood moon”? It’s like watching the moon slowly disappear, then suddenly it appears fully round, but red.

So there you have it,

a summary of all my Alberta night sky adventures so far. It’s very easy to overlook our home area, as we dream of all the far-off destinations abroad that we want to see and experience for ourselves. But there are definitely hidden gems located close to home, no matter where you call home!

I encourage you to explore the area around your home, and see what’s off the beaten path. Do you know of any places within a day’s drive where you can go when you just need to get away for a bit? If you have a story (or two) about a hidden gem that you have discovered, I’d love to hear about it! If you don’t mind sharing it publicly, please share your story in the comments. However, if you’d like to keep that location a hidden gem (which I totally understand), I’d love for you to share your story with me by sending me a message from my contact page.

Till next time, keep dreaming big!

» Jamie

“Never let your memories be greater than your dreams” – Douglas Ivester”